Everyone has had the experience of reading a novel inspired more or less by the author’s life and wondering which elements are “real” and which are fiction. It’s an exercise that can lead you to a level of truth or lead you astray; it can enrich your reading experience or take you out of the author’s carefully constructed world.

As a reader, I’m guilty of imagining autobiographical content even when it may not be there. How can an author not write about what she knows best? Even in the most fantastical fiction, the author is surely articulating her own experiences and opinions through her characters, be they axe murderers or aliens. But it’s probably because I have written so directly from my own life that I assume others do, too. It’s my literary comfort zone.

As a newly published writer, though, I’m quite outside my comfort zone. After keeping New Old World under wraps for three decades, it’s exciting but also a bit of a shock to have my friends and family reading it and talking about it. I feel exposed, but not because the details of my life are on display—I’m generally pretty open about all that. My discomfort has more to do with the conundrum I unwittingly created for readers who know me well. Almost to a person they’ve reported being distracted by the task of unraveling me from my protagonist Ticonderoga Fox. Whether it’s an elective or an imposed task, it seems to have interfered with their immersion.

My not very admirable first impulse is to apologize—for using my life as source material and then for tweaking it just enough to make it weirdly unfamiliar. The result is a hybrid Ti-Cynthia that I’ve unleashed on my friends and family. Those who have finished the book have been gracious and complimentary but also full of questions, which I try to take at face value and not as cloaked criticism. This is not to say that I haven’t enjoyed the various coffees and e-mail exchanges I’ve had with friends, where I’ve done some voluntary decoding, asked questions of my own, and reassured them that I’m still the same person they thought they knew before I messed with their minds. It’s more fun than I expected to talk about what I’ve written.

A few readers have said they were “hooked” from the start because they enjoyed the quality of writing or found the family intrinsically interesting. But I need to pay attention to those who have reported that the momentum doesn’t really pick up until somewhere in England or France. Is that because they’re busy with the biographical sorting game? I’m heartened by people who made it to the end and said that the payoff is worth the early investment of time and effort. I’m also encouraged by a couple of readers who don’t know my past well and have had smoother sailing through the early chapters and beyond.

But there’s the nagging concern that if my story had been compelling enough, my friends would have been able to resist the comparisons. Or maybe the real culprit is the choice I made to start the novel out slowly, not mid-action, giving readers too much time to ponder where the book is going—and to wonder whether I really had an uncle who was a photographic mentor or a father paralyzed by grief. (Nope on both!)

It probably doesn’t help that I’ve consciously played with genre, using different voices, viewpoints, and narrative distances to blur the line between novel and memoir. I will write more about these choices and devices in my next post.

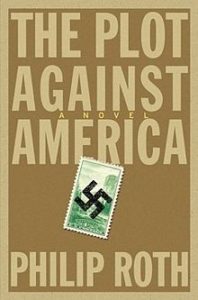

For now, I’d like to  bring a revered American author into the discussion, someone who’s a pro at using his life as a springboard. This past year I picked up Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America for its political prognostication, not for its autobiographical content. My first clue that Roth had drawn on his own family was seeing that the narrator’s name was Philip Roth! This is part of the cheeky, post-modern, 21st-century trend of authors creating protagonists who bear their own name, like avatars in video games. I haven’t read much Roth, but it didn’t take much Googling to learn that Philip and his brother Sandy and their parents lived in a Jewish neighborhood in Newark during the 1930s and ‘40s, just as described in the novel. Of course I idly speculated about whether the real Philip had had a beloved stamp album and a live-in cousin who lost a leg in the war, but any issues of verisimilitude were of no consequence once Roth launched into the central “What if?” of the novel: What if Charles Lindbergh had aced FDR out of his third term as U.S. President, and the national hero and Nazi sympathizer had gone on to be a puppet of the Third Reich? At that point Roth’s family became every Jewish family dealing with anti-semitism, deciding how to resist, and being whisked off to work camps for their own “protection.”

bring a revered American author into the discussion, someone who’s a pro at using his life as a springboard. This past year I picked up Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America for its political prognostication, not for its autobiographical content. My first clue that Roth had drawn on his own family was seeing that the narrator’s name was Philip Roth! This is part of the cheeky, post-modern, 21st-century trend of authors creating protagonists who bear their own name, like avatars in video games. I haven’t read much Roth, but it didn’t take much Googling to learn that Philip and his brother Sandy and their parents lived in a Jewish neighborhood in Newark during the 1930s and ‘40s, just as described in the novel. Of course I idly speculated about whether the real Philip had had a beloved stamp album and a live-in cousin who lost a leg in the war, but any issues of verisimilitude were of no consequence once Roth launched into the central “What if?” of the novel: What if Charles Lindbergh had aced FDR out of his third term as U.S. President, and the national hero and Nazi sympathizer had gone on to be a puppet of the Third Reich? At that point Roth’s family became every Jewish family dealing with anti-semitism, deciding how to resist, and being whisked off to work camps for their own “protection.”

In New Old World I’ve also introduced a family that has some parallels with my own, and then posed multiple “What ifs?”. For example, what if a woman grew up without a mother and that absence affected her life decisions, her relationships, and her thoughts about motherhood? What if she had a crisis while traveling that turned her life around and showed her how to deal with grief at last? They are intimate questions, not political ones, and the answers are personal, not dystopian. But, like Roth’s “What ifs,” they took me outside the limits of my life and served to address larger truths that might speak more universally than my own story could have.

Roth anchored his speculative novel in the reality of his own family, then told a bigger story that not only had repercussions for that family, their neighborhood, and the nation, but continues to serve as a cautionary tale in these Trumpian times. As far as I know, Roth was never apologetic about using his own familiar demographics as his starting point in this and any number of novels. So why is it difficult for me to admit that I’ve written a character so much like me and a story based on some of my own experiences? Is it the suspicion that an author, especially a woman and a first-time novelist, isn’t really being creative if she doesn’t invent a story out of whole cloth? It’s also tempting, as the world shudders under this newest populist surge, to dismiss a very personal story as not relevant or meaningful.

I had gone into this project wanting to better understand a big transition in my life; but I never fully achieved that understanding because the novel took off in other directions, posing different questions with different answers. Would it have been more honest and perhaps instructive, to write a memoir instead of a novel and stick to the “facts”?

In my mind, I didn’t need to choose between novel and memoir—I tapped my life and created something new. I knew my story needed something more than randomness to hold it together—it needed new contexts and a different climax in order to flower into an engaging work that would speak to other human beings on its own terms. So that’s what I did for the sake of a wider audience (commercial viability never having been a goal).

I’ll stick my neck out here and submit that a semi-autobiographical novel should be viewed as total fiction if that is the author’s intention. But the author can’t simply label it a novel—she has to earn the right to that genre by telling her story both universally and specifically enough to keep readers in her dream. If they’re distracted by real-life similarities, perhaps there’s something else wrong, technically or stylistically. But before I jump to conclusions or start rewriting, I will wait patiently for input from strangers who bring to the book only the desire to be captivated by another stranger. It would be nice to have a professional critic weigh in, too.

In the meantime, it may be useful for my readers, both strange and known, to think of New Old World as a puzzle. Not the riddle of who’s who or what’s real, but a series of interlocking story pieces that all fit together into a complete picture by the end. My hope is that readers can relax and have fun handling the individual pieces, no matter how much they look like me.